Claimant's attendance at hearing for cross examination

It is important to note that in neither Rabot or Briggs were the claimants in attendance to be cross examined and it appears that DJ Hennessy based her assessment of the non-tariff injuries from the medical evidence alone. There isn’t for example any reference to witness evidence of the claimant.

We have always advocated that it is preferable for the claimant to be in attendance and the case heard in the claimant's local court, and that remains an area of focus to hear actual evidence around the extent of the additional injuries.

This is likely to become a contentious issue moving forwards as generally claimant solicitors object to their clients attending in person. There may well be satellite litigation in respect of this point. It should be remembered that the OIC process was not designed to mirror the current stage 3 of the MOJ process but align with the small claims track process, when the claimant does attend. For example in a £495 tariff claim for a five month whiplash injury the claimant MUST attend the hearing in person if they are seeking an uplift for exceptional circumstances. The sum at stake in this example is £99 but the principle is that the claimant should be present to give evidence as to why an uplift is applicable. It therefore seems perverse that in an additional injuries matter where the sum at stake is much higher the claimant should not attend.

The comments of some judiciary in recent judgments suggest that there may be a need for increased clarity around the differences between MOJ stage 3 and the OIC small claims track process.

Plausibility of additional injuries

What is disappointing in Rabot and Briggs is that there was no discussion in either court as to how in these low value minor claims the claimants sustained soft tissue injuries to the knees with a prognosis of four to five months in Rabot and six months in Briggs.

Whilst there was a great deal of discussion about the badminton analogy in the Court of Appeal, a more powerful analogy might have been how quickly bruising/soft tissue injuries to the knee following an impact with a coffee table resolve compared to a similar type of injury sustained in a road traffic accident. Also there was no discussion as to how these claimants had actually banged their knees in the collision and the plausibility of the same.

The medical reports we are seeing provide for lengthy prognosis periods for bruising and very minor impact injuries of up to 6 months and more which stretch clinical credibility and are open to challenge. It is also often difficult to reconcile the type of injuries such as a sprained ankle to the collision itself. On board vehicle data and Telematics is likely to be increasingly leveraged as insurers seek to test claimants' credibility, and again the usefulness of such evidence is likely to lead to further satellite litigation.

Additional injuries frequency

We have always maintained that the key to challenging non-tariff injuries is in relation to causation and the mechanics of the accident and the cross examination of the claimant. This strategy remains sound and is crucial to defeating, what we believe, will be increased claims frequency for non-tariff injuries in light of the judgment.

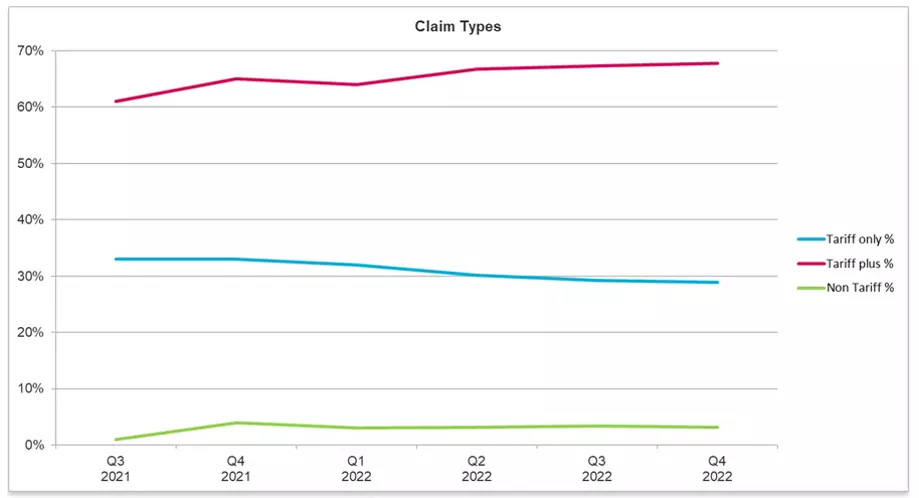

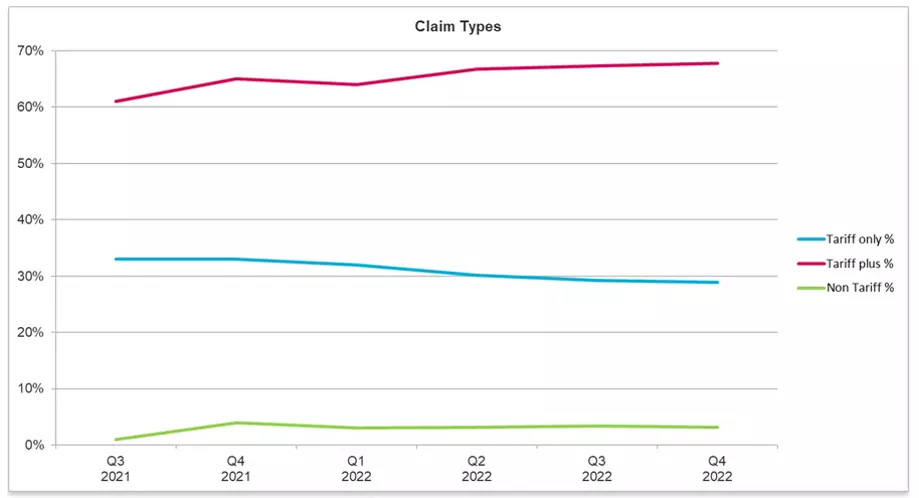

The latest OIC data shows that additional injury frequency reported at SCNF disclosure has steadily increased since the OIC was introduced.

In Briggs, disappointingly the award of DJ Hennessey was increased by £700 with only £340 being deducted for the overlap, less than 9% reduction.

As the Court of Appeal has made it clear that the maximum deduction for the overlap can be no greater than the tariff amount we are likely to see smaller reductions for overlap in the future and this coupled with an increase in additional injuries frequency will undoubtedly increase the claims for general damages.

For those claimant solicitors who rely on deducting a percentage of damages for costs, the difference in a claim where additional injuries are claimed is stark.

A six month tariff injury would equate to a deduction of £123.75 against a deduction of £750 if the total award including mixed injuries amounts to £3,000.

The intention of the reforms was to reduce both the frequency and cost of whiplash claims in order to lower the cost of insurance for consumers. Up to now the OIC has delivered in terms of frequency reduction but the risk is that claim farmers will come back into the market now that they have greater clarity around the potential value of claims, and those initial gains will be lost.

Medical reports

The present OIC position is that a large number of medical reports have not been uploaded on the portal pending the outcome of the judgment.

We have seen a change of approach by some medical experts in recent months with reports containing more information including mechanics, causation and pain, suffering and loss of amenity of the non-tariff injuries.

We are likely to see medical reports provide more detail of the pain, suffering and loss of amenity caused by the additional injuries. In neither Rabot nor Briggs could DJ Hennessy discern any particular difficulty caused by the knee injuries albeit they were said to be painful to a degree over a period of time.

Overlap

Going forward overlap reductions are likely to be modest and damages awards will be higher as a result of this and the anticipated increase in additional injuries. This in effect will bring awards for damages more in line with the pre 31 May 2021 figures.

Will we see prognoses for whiplash remain fairly static as the longer the prognosis the more that can be deducted from the additional injuries by overlap? It will be interesting to see.

MOJ v OIC

One other concern we have is that we are likely to see more claims commence in the MOJ portal with claimants' solicitors arguing that there were reasonable prospects of the claimant recovering more than £5,000 for personal injury. This is likely to be an increasing area of contention going forward.

Quantum disputes

There is clearly going to be more disagreement between the parties on valuations, resulting in more cases proceeding to court on quantum. That said, if you can keep appropriate cases in the OIC you can continue to benefit from the non-costs bearing environment.

The Consumer

One other disappointing aspect that was not mentioned in the Court of Appeal is the impact that this decision has on the consumer and how the benefits of the reforms are being eroded. The primary objective of reducing insurance premiums will not be met as the anticipated savings will not have been achieved. This needs to be included in the lobbying agenda for further change.

Lobbying

We will continue working with the insurance industry through our seats on various bodies and working parties. Separately we will continue to challenge spurious claims ensuring that full arguments are before the courts and reporting cases to support lobbying.

Global

Australia

Australia

France

France

Germany

Germany

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Poland

Poland

Qatar

Qatar

Spain

Spain

UAE

UAE

UK

UK