The allocation of licenses, concessions, and contracts for exploration and extraction has been opaque, thus, creating opportunities for corruption (1). Extractive projects are often based in developing economies, including in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, where “some business could not in practice be transacted without [bribery].” (2) Against this backdrop, the way we perceive corruption has evolved from bribes being “tax deductible as a production cost” to being a “global evil” that needs to be eliminated. (3)

In addition to international conventions seeking to combat bribery and corruption (4), there have been initiatives specifically aimed at targeting corruption in the extractive sector. For example, the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo has committed to making all mining contracts public within 60 days of signing, by publishing them in official government gazettes, ministry websites, and at least two Congolese daily newspapers (5). Further, the Republic of Ghana has implemented stricter environmental regulations, compliance protocols, and enhanced monitoring mechanisms designed to mitigate corruption risks. As a result, companies listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange are required to adhere to the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure Guidance Manual. Additionally, the Bank of Ghana has introduced Sustainable Banking Principles, which provide financial institutions with guidelines to promote sustainable practices (6). A global coalition of governments, companies, and civil society organisations has also set up the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (“EITI”), which seeks to reveal payments made and received for natural resources to foster an environment where both companies and governments can be held accountable for their actions (7). Responding to this development, businesses have also started adopting ESG policies driving towards zero tolerance for corruption and programs designed to prevent and detect corruption, including due diligence and whistle-blower procedures (8). As seen by these initiatives, the time has come for extractive businesses to respond to modern calls for social responsibility and sustainability.

In these global efforts, arbitration can also play a pivotal role in combating corruption, by providing a neutral platform for resolving disputes that are untainted by domestic political and judicial interference. This impartiality is critical in ensuring fair outcomes in corruption-related cases. Critical to this effort are also the arbitrators themselves. Indeed, arbitrators possess broad discretion in conducting proceedings, by being allowed to deny their jurisdiction (9), find claims inadmissible (10), or dismiss the claim if investments or contracts have been tainted by corruption (11). Arbitration awards also serve as an effective deterrent against corruption. Per the New York Convention, these awards are currently enforceable in 172 countries (12). This enforceability is crucial for holding parties accountable and ensuring compliance with anti-corruption measures. Indeed, the (un)enforceability of rights and obligations for such investments can be an effective enforcement mechanism for the industry to make good on its promises to fight corruption.

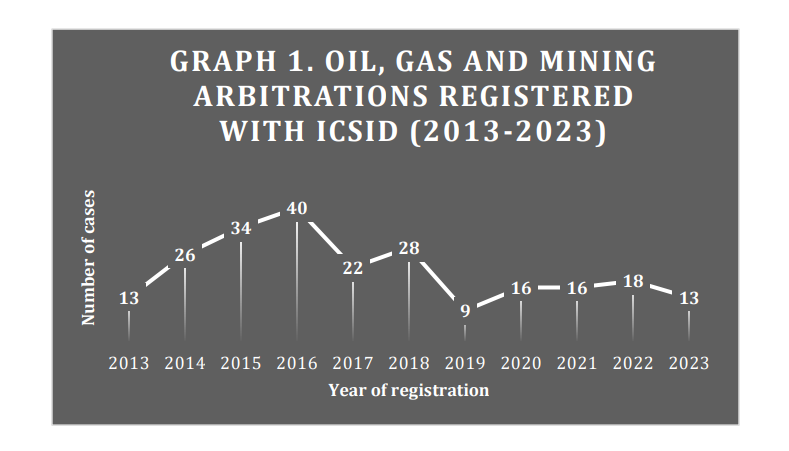

The role of arbitration in fighting corruption is paramount, particularly because a consistently high number of (known) arbitration cases involve the extractive sector. As showcased in Graph 1, in the past 10 years, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) registered 235 disputes involving the oil, gas, and mining sectors: (13)

This article surveys existing arbitration practices to elucidate how arbitration can help in promoting a zero tolerance for corruption in the extractive sector with a particular focus on two of the most significant decisions in extractive arbitration to date: the investor-state dispute, Glencore v. Colombia (I) (14), and the commercial arbitration dispute, P&ID v. Nigeria (15).

Through an exemplification of this case law, this article delves into the intricate issues underpinning the evidential burden for corruption allegations and the role that arbitrators can play in investigating bribery and corruption. It concludes by considering the broader implications of these decisions for future arbitration practices involving state parties.

To advance this argument, the paper will proceed in six parts. Part II. sets the context, by describing the legal orders relevant for consideration where corruption is alleged or suspected in an investment dispute. It also discusses the significance of various rules and the segmentation of law around this issue, such as the burden of proof and arbitrators’ role in investigating corruption. Further, it contends that arbitrators have broad discretion in conducting proceedings and can order evidence production or draw adverse inferences from a party’s failure to provide requested documents. Despite these discretionary powers, we observe that arbitrators frequently deviate on whether and in what circumstances they have a duty to investigate corruption allegations sua sponte if neither party pleads corruption as part of their claim or defence. Finally, this part considers the standard of proof, ‘connecting the dots’, and ‘red flags’ in the context of the evidential burden to prove corruption in extractive arbitration. It argues that arbitrators show varying degrees of willingness to infer corruption from circumstantial evidence.

To illustrate the divergent views on the burden and standard proof, part III. moves to a discussion of Glencore v. Colombia (I) where the Tribunal dismissed Colombia’s allegations of corruption, and arguably favoured the level playing field to avoid being complicit in the evasion of fundamental policies.

In contrast to this ruling, part IV. presents the English High Court judgment, which set aside an arbitral award in P&ID v. Nigeria on the basis of corruption. It contends that the Court did not adhere to its conventional approach within its supervisory role due to the case’s highly unusual nature and the broader implications it could have for arbitration as a dispute resolution process.

Along these findings, part V. suggests that, with more responsibility and the public interest in mind, arbitration may play a vital role in ensuring fair management of natural resources, by providing an impartial and efficient means of resolving disputes, balancing the interests of all parties involved, and promoting transparent practices.

Read the full journal at McGill Journal of Dispute Resolution.