Introduction

On 2 February 2021 during a meeting of the Health and Social Care Committee, which was taking oral evidence on the safety of maternity services in England, witness, Nadine Dorries MP (Minister of State for Patient Safety, Suicide Prevention and Mental Health) confirmed that the Department of Health and Social Care "..are looking across the NHS…not just maternity, at how issues of no-blame, no fault compensation and clinical negligence are treated."

Another witness, William Vineall (Director of NHS Quality, Safety and Investigations) subsequently confirmed a commitment to improve patient safety and tackle the rising costs (£2.3 billion) of clinical negligence by publishing a consultation this year (2021).

With significant tort reform now firmly on the UK Government's radar, this article considers the context (why now?) as well as the pros and cons of a no fault compensation scheme system in anticipation of the Government's imminent consultation.

The Context

The UK already has a no fault system operating for harm caused by vaccines in the form of the Vaccine Damage Payment Act 1979, which provides for a single, tax-free payment of £120,000 for those seriously disabled as a result of a vaccination against one or more specified diseases. From 31 December 2020, this now includes coronavirus vaccinations, pursuant to the Vaccine Damage Payments (Specified Disease) Order 2020, SI 2020/1411. Whilst at a macro level the global pandemic has shown us just how important healthcare is and the public commitment to protecting the NHS, it has also generated immense financial pressures that make a review of current costs and financial provisions now imperative. The statistics provided by NHS Resolution (Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20) confirmed that the provisions for claims against the secondary care system alone in England were £82.8 billion. There has been much concern that the pandemic will generate more claims and expense for the NHS and private providers, leading to calls for a prohibition of COVID related clinical claims. This has not gained traction as yet, possibly as the evidence to date is that clinical negligence claims actually declined in 2020 and might not 'boom' in 2021 for a range of reasons including 'sympathy' for healthcare practitioners.

The other element to factor in to the timing is the Government's focus on patient safety. Positive steps such as the introduction of the Patient Safety Incident Response Framework emphasise the importance of appropriately investigating an adverse healthcare event to ensure a culture of learning not blame, which in turn should deliver a reduction in the number of claims. In counterbalance to that, however, in 2020 we saw a number of reports, such as the Cumberlege Report (First do No Harm), Ockenden Report and Dr Kirkup's analysis of 'The Life and Death of Elizabeth Dixon', which demonstrated an absence of learning and fundamental failures to listen to patients. Whilst Baroness Cumberlege's calls for a Redress Agency in the First do No Harm report were not fully embraced at the time, there does now appear to be an enthusiasm for fundamental change.

That leads on to the key question, if the objectives are to achieve financial savings and a better quality of care, then could a no fault scheme deliver just that?

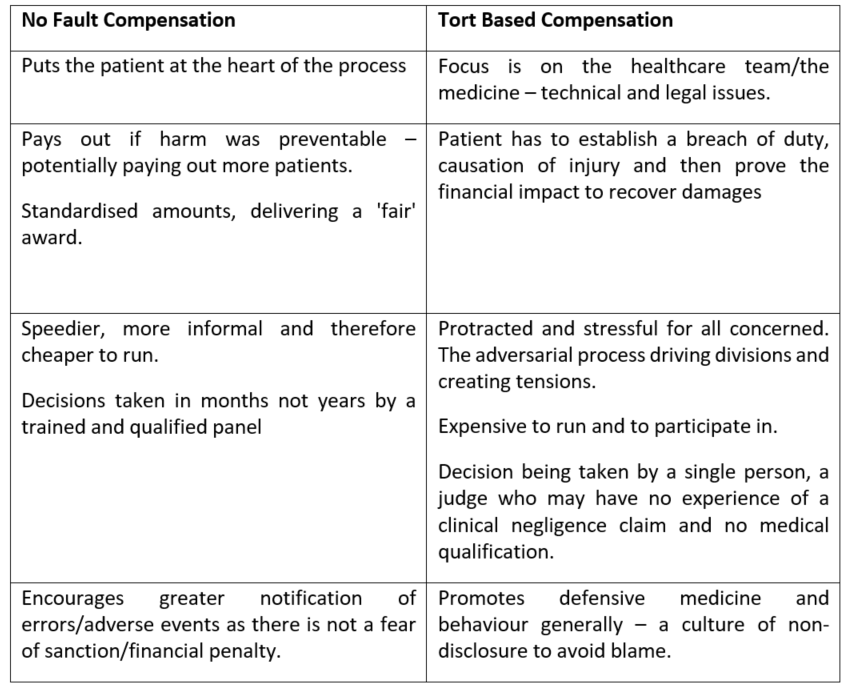

The Benefits of a No Fault Scheme versus a Tort Based Compensation System

The respective benefits of each scheme are summarised below:

As ever, however, the devil is in the detail and as researchers such as Vera Lucia Raposo have demonstrated ('The unbearable lightness of culpability: the compensation for damages in the practice of medicine', 2016 Saude Soc. Sao Paulo v. 25 n.1 p.57-69) a no fault system can be seductively attractive, but is far from a perfect model. Challenges include: –

- The lack of accountability – creating an environment where clinical standards deteriorate

- It requires a robust social security system to pick up the absence of 100% compensation

- Financial savings will only be made if the community it is introduced to is not committed to litigation.

The Nordic countries (most notably Sweden) and New Zealand currently operate no fault systems for clinical negligence claims. There are, however, important differences in how funding operates and the availability of alternatives. There are also differences in scope, Sweden includes state and private healthcare which is not something that the UK Government appear to be considering, but such an approach would remove indemnity concerns which were a focus for the Government's 2018 consultation on appropriate clinical negligence cover. This leads us on to the final question of logistics and implementation.

How could a no fault scheme be established and what could it look like?

- A fund would need to be established to administer the scheme and make the payments. The obvious source being tax payers, the alternative being practitioners/providers via an insurance fund.

- A date for implementation would need to be set, (presumably not operating retrospectively), which would trigger a raft of notifications to avoid being a 'guinea pig' for the new scheme.

- Costs would be incurred in running the administrative system, communications and decision making. Whilst software could deal with initial notifications and fraud screening, human input would be required for panel decision making which would presumably be attended by the patient who would respond to questions.

- Criteria would need to be established as to how patients would qualify for a pay-out and the amount, which generates further questions as to the avoidability of harm criteria and how different that really is from negligence.

- Whilst in New Zealand a patient cannot choose to litigate if they do not want/like the alternative of no fault compensation (which is designed to restrict access to the courts), here in the UK, such an approach would trigger challenges based on the European Convention of Human Rights (Brexit locking the UK into continued membership and compliance). The UK government would therefore need to support a dual system and meet the costs that this generates.

Conclusions

If the objective of introducing no fault compensation is to save the UK Government money from clinical negligence claims against the NHS, then the bean counters will need to be creative so as to demonstrate that such a system would deliver that result in the short, medium or indeed long term. Focus has been on the costs of maternity claims and it may be that, as the most expensive cases to settle, they are the focus and indeed starting point for such a scheme. Returning to the information shared by Nadine Dorries on 2 February 2021 with the Health and Social Care Committee, however, she was clear that her department were looking across the NHS in the round, not just in maternity. We await the debates and consultation with interest.

For further information please contact Vicki Swanton, Partner, Healthcare.